WEST MICHIGAN AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC AND HISTORY

INTRODUCING KIM RUSH: BIOGRAPHY AND RESEARCH PROFILE PAGE

Kim Rush was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan on October 8, 1951.

Kim’s interest in blues music began while attending high school in the late 60s . Friends Brehm Rypstra and Jeff Bulson introduced him to blues-oriented recordings like Paul Butterfield Blues Band and The Electric Flag. He began to attend concerts that featured blues music, such as B.B. King at Fountain Street Church and Bukka White, performing at Grand Valley State College in 1972.

While attending Grand Valley, Kim sang and played blues and rock music, and was eventually honored to perform with Trumpet and Sun blues recording artist Otis Green .

Kim also began reading any historical information that he could locate about blues music from magazines such as Living Blues, Juke and Blues Unlimited. He also read numerous books about blues music history, trying to absorb key information and obtain an understanding of the history of this musical genre.

In the late 1990s, Kim and his brother Stephen visited Chicago to explore and photograph blues music landmarks like Muddy Water’s former apartment and home, Maxwell Street Market, various Chess Recording studio locations, as well as locations of clubs where Elmore James, Tampa Red, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, etc. performed. While visiting Muddy Water’s pre-1973 home, Kim and Steve met and conversed with Charles Williams on the front doorsteps. He is Muddy Waters’ step-son, and he lived with Muddy from 1947-1973.

In 2000, Stephen Rush obtained a grant to return to Chicago in the summer and winter to record 24 hours of interviews with Charles Williams. These interviews have been transcribed. MISSING IN ACTION

In 2002 Kim wrote a short online biography about blues harp genius Carey Bell which can be read at www.furious.com/PERFECT/careybell.html .

Kim’s historical research projects include researching Grand Rapids African-American history and music which he began in 2003, as well as compiling a listing of historic blues clubs that were located in Detroit from 1940-1980.

In December 2004, Living Blues magazine(issue # 175) published his article that briefly focuses on findings of his earlier Grand Rapids blues music research. Living Blues magazine is an excellent source of information concerning blues music history. Here is a link to their website: www.livingblues.com

Here is the article by Kim, courtesy of Living Blues Magazine:

He has also written an article about Michael Bloomfield with David Dann, providing photography and background history about blues guitarist Michael Bloomfield. Click here to read it: http://mikebloomfieldamericanmusic.com/homes.htm

The following is an article written by John Sinkevics for the Grand Rapids Press concerning a presentation given by Kim at the Gerald Ford Museum:

Published: Sunday, March 14, 2010 By John Sinkevics The Grand Rapids Press

With Chicago’s breeding-ground hotbed for blues guitarists and singers just a short tour bus ride away, Grand Rapids’ love affair with the blues makes perfect sense.Since the 1980s, I’ve been impressed by the city’s appetite for this seminal music, evidenced by elbow-to-elbow crowds cheering Chicago’s Big Time Sarah at The Silver Cloud on the city’s West Side or the illustrious Eddie King & the Swamp Bees making a stop at downtown’s intimate Rhythm Kitchen Cafe.

| Giving Up the Blues for Gospel |

||

| The Story of Women Blues Singers in Grand Rapids Presentation by local historian Kim D. RushWhen: 7 p.m. ThursdayWhere: Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, 303 Pearl St. NW

|

||

While these establishments have since bit the dust, the blues tradition continues at clubs such as Billy’s Lounge in Eastown and in WLAV-FM’s wildly popular Blues on the Mall series, which draws thousands downtown on Wednesday nights every summer.

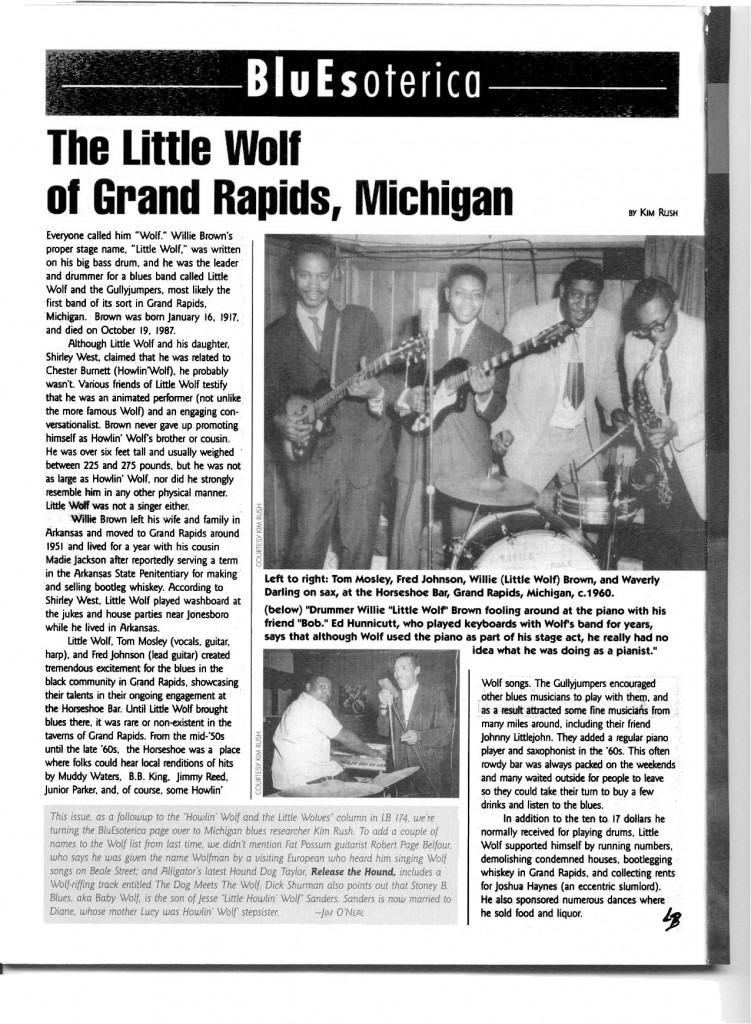

But decades before any of these were even gleams in their promoters’ eyes, there was drummer Little Wolf and the Gullyjumpers playing regular blues gigs at the Horseshoe Bar on Grandville Avenue north of Wealthy Street SE. The club was a nightlife hot spot in the 1950s and 1960s.

And consider some of the blues greats who graced Grand Rapids during this period:

— The legendary B.B. King and Muddy Waters, in the years before African-American artists found acceptance with white audiences, played the Rose Room at 814 S. Division Ave.

— T-Bone Walker, Ray Charles and Bobby “Blue” Bland entertained crowds upstairs at Roma Hall, near the Rose Room.

— John Lee Hooker and Alberta Adams performed at the Crispus Attucks American Legion Post 59 on Commerce Avenue SW.

Those are the kinds of local blues history nuggets that get Kim’s heart pumping and keep him up late at night, poring over old posters and photos, going through reels of newspaper microfilm and interviewing anybody who recalls anything about eras gone by.

“This has become more of an obsession than the music,” conceded the 58-year-old Grandville man, who’s spent more than seven years tracking down the history of Grand Rapids blues musicians. So far, that’s led to an article written by Rush about Lil’ Wolf, aka Willie Brown, for Chicago’s Living Blues magazine.

It also landed the blues hound on the schedule this week for the Greater Grand Rapids Women’s History Council’s lecture series during Women’s History Month.

While there haven’t been many female blues singers in Grand Rapids’ music pipeline, a few certainly have played a role in the city’s rich musical legacy, including singers Lizzie Thorbs and Eddie Ingram.

Rush said Thorbs, who played house parties in Grand Rapids in the 1950s, taught her nephew, local musician Ed Hunnicutt, how to play piano. Ingram sang at times with Wolf’s band at the Horseshoe, which formed the center of Grand Rapids’ African-American blues universe a half-century ago.

The city’s music scene, Rush observed, was “extremely segregated,” so clubs like the Horseshoe served an almost exclusively black clientele.

Lil’ Wolf, who moved to Michigan from Arkansas in the early 1950s, became a blues institution at the Horseshoe, which charged a 50-cent cover to patrons, according to Rush.

Wolf filled out his house band with exceptional local musicians such as Ed Hunnicutt (guitar, harmonica, piano) and Tom Mosley (guitar, harmonica), who still live in Grand Rapids and have been instrumental in helping Rush with his blues research.

But Rush’s findings reach way beyond the music itself.

“I like to create a picture or conception in my mind of what was actually going on in the black community while it was totally segregated, based on what I have learned from talking to the people that have lived it,” said Rush, a longtime blues maven who himself sang and played bass in Grand Rapids bands from 1970 to 1987.

“Learning more about the components of this total picture is like exciting detective work. I don’t think most white people, including me, have a substantial understanding of what black people endured and the pressure they lived with.”

Rush, a graduate of Forest Hills High School and Grand Valley State College, works as lead finisher in the maintenance department for Spectrum Health’s Blodgett Hospital. So, he’s done his research after hours in libraries and music union offices, over the telephone, and in the homes of those with memories of days gone by.

For Thursday’s presentation, he’s supplemented those findings with interviews of more contemporary Grand Rapids artists, including talented female singers Mona Sallie and Roberta Bradley. Rush said while neither might be considered a blues purist, both are “totally capable of delivering a great blues” song.

Sallie said she sang gospel music at church in her youth, but took to the blues when she first became a club performer.

“I started off as a blues singer. (But) there’s not much money in singing the blues,” said Sallie, who fronts the Grand Rapids soul group Mona Sallie & the Sounds of the Motor City.

That’s always been the rub with the blues: most performers never see a financial payoff. That’s why Sallie appreciates the kind of intense research Rush has done to shed more light on Grand Rapids’ blues pioneers.

“I think we’re so caught up in the right now, we’ve got to remember where we got our foundation from,” she said. “Blues is the roots.”

On March 18, 2010, the Grand Rapids Historical Society hosted a presentation by Kim called “Giving Up the Blues for Gospel: A History of Women Blues Singers from Grand Rapids.” A documentary video bearing this same name was shown at this event. Here is the accompanying speech about the history of jazz and blues that Kim provided that evening:

“ Blues music is essentially African and African- American in origin. You probably overheard an example of it as you entered this auditorium tonight. Blues is typically folk music, not music that is created in universities and music schools. It is not normally created or performed by classically trained musicians. Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and BB King are popular examples of blues musicians.

Contemporary jazz is more complicated than the blues. Miles Davis, Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald are common examples of jazz musicians. Many modern jazz musicians have received formal classical music training.

But before the 1940’s, when jazz musicians started creating their music specifically for the pleasure of intense listeners and for concerts, there was not such a marked difference between the sound of jazz and blues. The blues was the basis for jazz in the earliest days of jazz performance and recording. Some argue that the blues is still the initial corner stone of all American folk music, including jazz.

So it’s probably not wise to maintain that there is a huge distinction between jazz and blues. Nor is it sensible to try to narrowly define either one of them. There is not one type or style of either blues or jazz music. I have never heard or read a definitive, totally satisfying answer to all of these questions, and it’s ultimately another one of those discussions that are best left to the academics and music experts.

During tonight’s program I aim to present women from Grand Rapids that have deeply embraced and performed this music called the blues.

I have been researching Grand Rapids African-American history for seven years, often concentrating on our local blues musicians. One of these musicians, Ed Hunnicutt, has generously contributed his time to introduce me to many people in the black community. I am totally appreciative that he did this for me. Without his knowledge and assistance, much of the material displayed in tonight’s program would simply not be available. An interview with him is included in the video you are about to see.

What we have discovered begins in the 1950s. At that time, performance of all blues music was primarily located in and performed by members of the African-American community. Our local black blues music scene probably reached it’s peak in the 50s and 60s at the Horseshoe Bar at 333 Grandville Avenue SW, though there were various other places where blues music was performed in Grand Rapids. Little Wolf and the Gullyjumpers were employed at the Horseshoe Bar as the house band. He and his band members openly encouraged women to perform with them. He occasionally hired Margaret LaMarr, a professional blues drummer from Gary, as his featured singer. Grand Rapid’s Eddie Ingram also sang with Wolf’s bands in the 60’s and 70’s. She is pictured sitting on the stage in a poster for a 1970s Roma Hall concert found in your program brochure. (SHOW BROCHURE). You will hear her tell her story tonight in the documentary that you will soon see. She is also the first woman that you will see at the beginning of the video, singing a familiar blues song called ‘Rock Me.’

Here’s a little more background about this documentary: Primarily, it’s 4 chronologically presented interviews about 4 different women blues musicians from Grand Rapids. Once you’ve heard Ed tell about Lizzie Thorbs teaching him how to play blues piano and his stories about other local women blues singers, we are introduced to Eddie Ingram. She discusses how she sang with her boyfriend’s band called Little Wolf and the Gullyjumpers, and also talks about a few other women blues musicians that she has seen perform in Grand Rapids. Then we proceed to the amazingly gifted Mona Sallie discussing her career as a singer. One of her blues-tinged gospel songs is featured at the end of the video. Though this style of music is somewhat different than the blues, it is clear that elements of the blues sound are noticeably retained in gospel music, as well as in jazz.

The last interview sequence is with Roberta Bradley, who entered the local scene with her blues singing prowess in the 90’s. Ed, Eddie, and Mona are all here tonight and will come onstage after the documentary is shown to be introduced to you and to answer your questions.

I did expend considerable time and effort trying to track down an exhaustive list of women blues singers for this program. I talked to numerous elderly retired musicians that I knew had performed in Grand Rapids from the 1940s onward. However, I do not want to give the impression that I believe that the results of this research are necessarily conclusive, nor am I suggesting that there were never any other women’s blues musicians in the history of Grand Rapids . Instead, I’d like to encourage you to assist me by offering corrections and providing new information about this subject.

My appreciation extends to the Grand Rapids Historical Society, the Grand Rapids Historical Commission, the Grand Rapids Women’s History Council and the Gerald Ford Museum for sponsoring this event. Huge thanks to Diana Barrett and Jo Ellyn Clarey for their welcoming and enthusiastic support of my research. Diana, Jo Ellyn and Maureen Penn also worked very hard to promote the success of this program.

Steve Smith is always very helpful with historical and recording information about blues and jazz. He also supplies me with data and pictures concerning historic buildings in Grand Rapids. When you have time please read his article on the inside of the handout that you received on the way in. (SHOW BROCHURE) The graphics on the covers and on the inside are identified at the end of the article.

Thanks to Kevin Johnson for technical assistance and friendship, to Jen Morrison and the downtown library Grand Rapids history staff for their willingness to help me find information, and my wife Janet Rush for her constant incredible support and assistance.

I’m going to stop with the credits, sincerely hoping that I have not forgotten anyone. It’s time to get to the program that you came to see. I certainly hope that you enjoy this documentary called Giving Up the Blues for Gospel. It’s a history of women blues musicians from Grand Rapids that eventually decided to embrace the church and it’s music. They have freely told their story in their own words, and in the way they wanted it known. “

Here is the text from the brochure that was handed out at this event which contains an article written by Steve Smith and Kim:

The life of a blues musician can be very difficult. It normally takes many years to reach the point where one is capable of competing with established blues players and singers. It is normally a career that leads to little success. For example, blues recording sales amount to less than 2% of current cumulative sales. The pay is generally low for performances. Good sounding equipment and instruments are expensive, as well as the maintenance costs associated with keeping them in good condition. Playing engagements are very scarce, especially in small markets like Grand Rapids. Musicians must be willing to travel often and relocate to make money.

The blues has been called “the devil’s music.” Yet ironically, blues singers often receive their early training in church choirs. Two considerable examples are John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters.

The program you will see tonight features a chronological oral history about women from GR that have sung or played blues music. Most of the women that we focus on in “Giving up the Blues for Gospel” have done just that, though none are compelled to express total contempt for the blues.

This is also the case with some nationally known blues recording figures. Thomas Dorsey, an author of both risqué blues and gospel songs, eventually worked at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago.

Likewise, Sippie Wallace, after enjoying great popularity in the 1920s as a blues recording artist, spent approximately forty years as a organ player and vocalist with the Leland Baptist Church in Detroit.

By 1919, prohibitive patent restrictions governing the recording processes were eased and new labels were created. Recording companies targeted niche markets. An era of “race recordings” also thrived in this same time frame, where black music was finally being marketed for black consumers. Even Thomas Edison was recording blues musicians!

Post World War I prosperity also played part in fueling the tremendous sales success of women’s blues recordings in the 1920s. Initially, in 1920, Mamie Smith recorded “Crazy Blues” and it was an unexpected hit. The recording companies responded quickly by exploiting this phenomenon and began to concentrate on marketing women’s blues recordings with predictable results. Sippie Wallace’s records on the Okeh label were good sellers. This small group of women blues singers in the 1920s also received notoriety as entertainers on a black theater circuit.

The onset of the Great Depression put an end to this decade long reign where women blues singers were more popular than men. Music historians tend to call this the “Classic Women’s Blues” era.

In the late 1910s and in the 1920s, jazz and blues were not typically acknowledged as separate in their identity, although they are certainly related musical styles. “Jazz” was assumed to be any modern popular dance music, especially if it was “hot” or “peppy”. “The blues” was a well known expression for feelings of melancholy or sadness or longing, and was understood to be a kind of popular song expressing these emotions that was played by jazz bands. Jazz is largely based on the blues, both then and now. Back then jazz was “low down” and “dirty,” just like the blues. People we currently consider to be “jazz” musicians, like Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet, supported blues musicians like Sippie Wallace on her early recordings. In the days of jazz infancy, it was recognized as popular dance music. Only after the 1930s, with the invention of a new form of jazz meant more specifically for listening or concerts, did it begin to sound very different than the blues.

In late 1945 or early 1946, Steve Smith’s father-in-law Don Patterson was finishing up his tour of duty for the U.S. Navy. Within that same time frame, he and his friends attended Club Indigo, located near the corner of South Division and Franklin. Providing the entertainment that evening was Lil Johnson, another black woman blues singer known for her 1935 hit called, “(Hot Nuts) Get ‘Em From the Peanut Man.” This upstairs dance hall was located at 746 South Division, was owned by the Russo family. They rented this space above their restaurant to Grand Rapids African-Americans for at least 30 years. James Brown, B.B. King and Bobby Blue Bland are all reported to have played there. So we can conclude that blues music has had an audience in Grand Rapids for many years, and that women blues musicians have certainly been vital and intrinsic to this history. (this article was written by Steve Smith and Kim Rush)

Front cover art is sheet music from Crazy Blues by Mamie Smith. INSERT

Poster to the right of the above article is from a c. 1970’s poster for a show at the Roma Hall (the musicians in the picture are L to R, Foots, seated in front is Eddie Ingram, seated in rear is Wolf (Willie Brown), Tommy Fry and Junior Bodie. INSERT

Rear cover is an advertisement from the 1924 Phonograph and Talking Machine Weekly for Sippie Wallace recordings on OKEH Race Records INSERT

Since, 2004, Kim’s research has expanded to include all Grand Rapids African American history, but he has certainly retained his interest in the musical culture and history of local black musicians. Currently, Kim is working on an article about the G.B. Russo family and their Roma Hall. Roma Hall was a rental space that was built by GB Russo c. 1930 and has been used for various events including concerts and dances that have featured Nat King Cole, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Al Green, Mary Wells, Major Lance and James Brown. The building was located on the north-east corner of South Division and Franklin, and was demolished in 1991.