Del Shannon was not the first West Michigan musician to a create a rock and roll record, but he was the first to become famous for doing so.

The following article, which details Del Shannon’s career history, is provided with gracious permission from its author, Brian Young, who is an expert concerning Del Shannon’s biographical data, and hosts an incredible website called Delshannon.com. Here’s a link to Brian’s website: http://www.delshannon.com/

THE DEL SHANNON BIOGRAPHY

By Brian Young, ©Copyright 2004

Del Shannon was one of the handful of American Rock ‘n’ Rollers of the 1960s to survive the crashing tide of the British Invasion. Among the few were Elvis, Dion, Roy Orbison, and Del Shannon.

Del Shannon was born Charles Weedon Westover on December 30, 1934 in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The son of Bert and Leone, his family lived in nearby Coopersville, a small and rural farming community just outside Grand Rapids. There, he would learn to play ukulele from his mother and grow up the oldest of three children. He had two sisters, Blanche and Ruth Anne.

Young Westover grew up listening to country and western music. His favorite artists included Hank Williams, Hank Snow, and Lefty Frizzell. The Ink Spots were also among his favorite, and he claims he learned falsetto from songs like We Three. Charles Westover bought his first acoustic guitar for $5.00. His fingers bled from it. He had no pick, just pieces of cardboard and dreams. At the age of 14, he walked to the Coopersville train station to await the arrival of his first new Sears and Roebuck guitar. He was proud of it, played it everywhere. “His guitar was his crutch,” explained Russell Conran, his former high school principal. “Charles played his guitar everywhere he went, at football games, in class, in the hallways, at noon hour, everywhere. I finally had to allow him time to play in the boy’s locker room, so that he wouldn’t distract his fellow classmates.”

“That’s where I learned all about ‘bathroom acoustics’,” Westover (by then Del Shannon) recalled in an interview with Dick Clark on ‘Rock, Roll, and Remember.’ “I would get this great echo sound. Later, when I bought an electric guitar and amp, I would set the amp on the toilet seat and play in bathrooms for hours and hours, just to get a great sound. You know, from bouncing off the bathroom tile.”

Westover was a small man, about 5-foot-six and 140 pounds. In high school, he was too small to play football, and if you couldn’t play football in Coopersville, you didn’t amount to much. Westover was the waterboy, who brought his guitar to the games to entertain. Young Charles was never quite popular with the girls in school. One day he asked a girl named Karen if she would go to the senior prom with him. She said yes. Two weeks later, as the prom drew nearer, she dumped Westover for another boy, one of Charles’ rivals. This put Westover in a huge depression he seemingly never recovered from, for many of the songs he would write later in his adult life would result from his feelings of early loss, hurt, and betrayal.

One day Charles Westover met Shirley Nash, a local Michigan girl. She came from a big family, six brothers and six sisters. Shirley first met Charles at the Coopersville theatre, where they were all catching a film with his friend Sonny Marshall. In 1954, he was drafted into the U.S. Army. “Jobs were hard to come by anyway,” Shirley remembers. “Chuck picked strawberries in the fields of Coopersville, and later drove a delivery truck selling flowers. We met at the theatre on Main Street in Coopersville. We spent a stint in Fort Knox, Kentucky, followed by a three year tour in Stuttgart, Germany.” In Germany, Westover joined the Army’s “Get Up and Go” radio program, and played guitar in a band called the Cool Flames. Standards of the day were the usual set list. Westover won a best musician award, not for his singing ability, but for his guitar playing. At Christmas time, the Westovers attended a holiday party at the Stuttgart orphanage, where they sponsored orphan children. This was an early sign of Westover’s compassionate side.

When his army service ended, Charles returned to Michigan with Shirley, settling down in Battle Creek, a town best known for its production of cereals, including Kellogg’s and Post. Westover worked at Brunswick Furniture hammering feet onto chairs as a production line worker. It bored the hell out of him. He soon graduated to lift truck driver but that bored him too. In 1958, he found a job by day selling carpets, working at the Carpet Outlet for a man named Peter Vice. By night, he found a part-time job moonlighting at a dumpy bar called the Hi-Lo Club. He was hired as a guitar player by then front-man Doug DeMott, who had organized a group called the Moonlight Ramblers. DeMott was a heavy drinker who had managed to release two failing singles, I’m Stepping Out Tonight b/w My Lonely Prayer in 1958 for Excellent Records (45rpm #805), followed by Fingers On Fire b/w Upside Down Boogie.

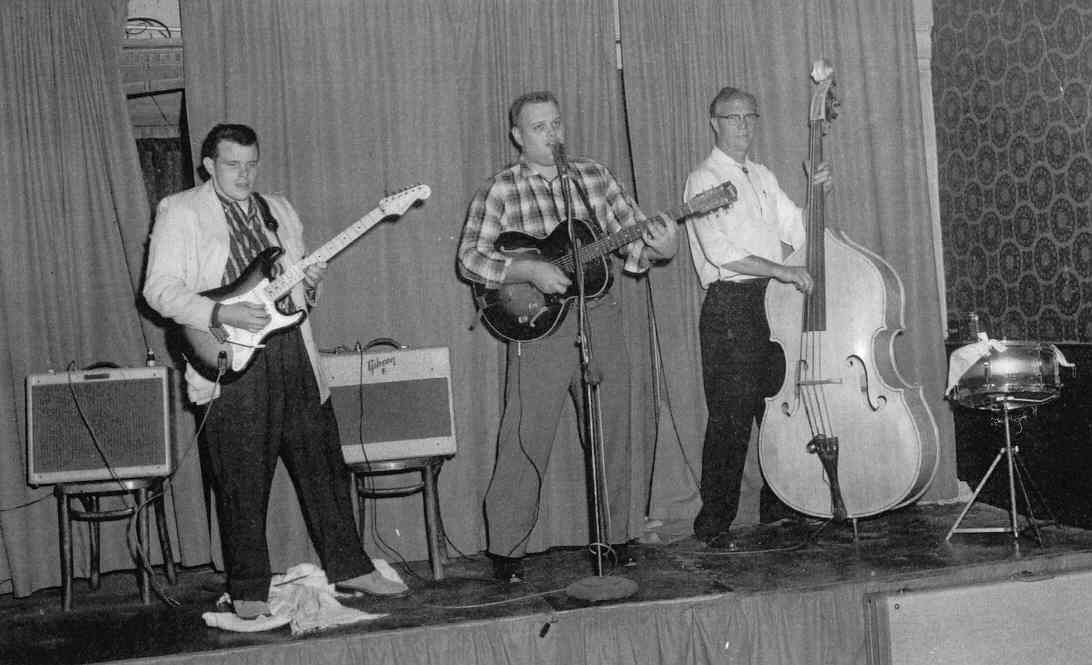

At the Hi-Lo Club 1958 in Battle Creek. Left is Del, middle is Doug Demott (singing), and right on bass is L.D. Dugger.

The Moonlight Ramblers consisted of DeMott as lead singer and lead guitarist, Charles Westover as rhythm guitarist, and Loren Dugger as bass player. DeMott was a good mentor for young Westover. He gave him the chance to sing a few songs on stage, play lead, and encouraged him to write songs. DeMott was soon fired by the Hi-Lo Club’s manager, Larry Gilbert, who hired Westover as the new front man of the club band. Westover gave himself the stage name Charlie Johnson and dubbed the new band the Big Little Show Band.

Westover made many friends as a guitarist and drinker at the Hi-Lo Club. Wes Kilbourne was a club regular and also worked with Westover at Brunswick. He played guitar also but wasn’t part of the band. He was part of the crowd however, and they would sing, play, and drink into the wee hours. Charlie Marsh, Battle Creek disc jockey extraordinaire, attended nights at the Hi-Lo frequently looking for talent. Marsh became Westover’s first manager. “I’m forgotten in the Del Shannon history,” says Marsh, “basically because I never did anything for him. I shopped demo tapes for him just like Ollie (McLaughlin) did, but Ollie was the one that got him the recording contract.”

Charlie Johnson and the Big Little Show Band began in late 1958. He kept Loren Dugger on bass, and hired two more players: Dick Pace on guitar, and Dick Parker on drums. Parker, then just eighteen, was a referral. Pace didn’t stick around long enough; with a large family to support, he left for California to work at Knott’s Berry Farm. Westover was in need of another guitarist, and hired Bob Popenhagen, a local guitarist who could also play left handed and play organ well. Popenhagen was a great addition to the band. He was well liked and in early 1959 he left to front a band at another Battle Creek bar, the El Grotto. This put Westover in need of another player. Drummer Dick Parker suggested that Westover call a man he knew who played accordion and piano. Westover declined. He wanted a guitar player. Parker pushed Westover to at least audition this organist, who had a little organ that made “other worldly sounds.” Enter Max Crook from Ann Arbor, Michigan, who attended college in Kalamazoo. Parker and Crook had met each other at a Battle of the Bands contest at Kalamazoo Armory. Crook arrived one night at the Hi-Lo Club to audition for the part of organist. He brought a little three-legged synthesizer he dubbed the ‘Musitron.’ Crook and his Musitron blew Westover away. He couldn’t believe the sounds he heard coming out of this little black box machine. “Man, you are hired!” Westover exclaimed.

This was the beginning of the new Charlie Johnson and the Big Little Show Band, and they became the hottest act in Battle Creek. Max Crook was a man who tinkered with everything electronic, and he became one of the first to record Westover’s compositions on tape, beginning with original tunes like Little Oscar, I’m Blue Without You, and Living In Misery. Westover and Crook laid down song after song. Instrumentals were written, and recorded on stage at the Hi-Lo Club, including Somethin’ Like Somethin’, G-Jam, Hi-Lo Boogie, and Hi-Lo Blues. Westover recorded Face of An Angel, and shopped it to two Chicago labels, Mercury and Chess, with the help from disc jockey, Charlie Marsh. Westover later explained “This was my first encountering of ‘the jive.’ They’d say they liked my stuff, and they would get back with me. But they never did. They never called.” Crook mentioned that he knew a disc jockey in his hometown of Ann Arbor, who could possibly help. The DJ was named Ollie McLaughlin, who had gotten Crook’s first single, Get That Fly/Orny, released in 1959 on Dot Records under the name of the White Bucks (the trademark footwear of Dot’s biggest act, Pat Boone). McLaughlin came in to the Hi-Lo Club one night after hours to hear some songs. He was black and in those days the Hi-Lo was an all white club.

Westover and Crook gave McLaughlin a few songs on reel-to-reel to take back with him to Detroit: Westover’s The Search and I’ll Always Love You, and Crook’s Mr. Lonely and Seventh Hour. McLaughlin took the demos to Harry Balk and Irving Micahnik of Talent Artists, Inc. on Alexander Street in Detroit. Their King-Mack Productions basked in the success of Johnny and the Hurricanes, a 5-piece instrumental group who had charted Red River Rock and Beatnik Fly. Westover and Crook met with Balk and Michanik at McLaughlin’s urging, and they sat down in July of 1960 and signed a contract to become both recording artists and composers for Talent Artists, who subcontracted them to Johnny Beinstock’s Bigtop Records in New York. In the back room, McLaughlin and Balk negotiated a deal on the music’s publishing, splitting it 50-50 between McLaughlin Publishing and Balk’s Vicki Music (named after his daughter). Balk and Micahnik gave Westover and Crook 2% royalties on singles released in the U.S., and 1% on releases overseas. Anxious to get on record, both Westover and Crook agreed and signed five-year contracts.

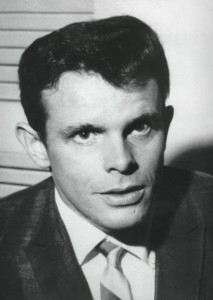

Balk suggested name changes for both of the newly signed artists. Charles Westover became Del Shannon, “Del” after a Coupe de Ville Cadillac that his carpet store boss drove at the time, and “Shannon” from a wannabe wrestler at the Hi Lo Club, a guy named Bob White, who wanted to use the name Mark Shannon. Since he never used it, Westover took the name. Max Crook took the name Maximilian, a clever king-like name that sounded authoritative.

As the newly christened Del Shannon, Westover was immediately flown to New York City to record his first single The Search/I’ll Always Love You. Balk produced the session, bringing in Bill Ramal, a young arranger and saxophone player whom he’d used for most Johnny and the Hurricanes sessions. There was a great string arrangement by Bill Ramal, but Shannon was too nervous in the studio and couldn’t get a good take. Balk decided to scrap the session, and that there was no hope for a single. Max Crook wasn’t used for this first session. His compositions Mr. Lonely and Seventh Hour were given to Johnny and the Hurricanes to record. They released just one, Mr. Lonely as the A-side coupled with Ja-Da on Bigtop Records in 1960.

Shannon, depressed about the failing session, was encouraged by McLaughlin and Balk to write something a little more uptempo. Shannon wrote songs such as Daydreams, The Prom, One More Time, Condemned To Die, and Honey Bee. Demo tapes were sent off to McLaughlin, who heard a snippet of a song called Little Runaway, which had been recorded over. McLaughlin asked Shannon and Crook to re-record the song. Little Runaway was re-recorded in Max Crook’s living room, along with another song, Jody. McLaughlin liked what he heard and drove to Detroit again to sit with Balk and Micahnik to negotiate another recording session. They refused. McLaughlin pressed hard, believing highly in the potential of this Little Runaway song. Harry Balk commented, “You know the problem with this song Ollie, is that it sounds like three songs trying to come together. What’s this little thing in the middle?” Ollie pushed, telling Balk and Micahnik that they would be missing out on a hit if they didn’t record this record.

Harry Balk called Shannon and told him that he would set up another session. Not banking totally in Shannon’s singing ability, he encouraged Max to write a couple of instrumentals to record at the session. Balk planned a split session, Del’s Runaway and Jody together with Max’s The Snake and The Wanderer. Balk wanted to record something specifically with Crook’s musitron, and this was it. Shannon and Crook made the long 700 mile trip to New York by car to record the session. It was the middle of winter, and the heater broke in the car. Del and Max brought their wives with them, Shirley and Joann. They wrapped blankets around them in the back seat to keep warm. Max was allergic to smoke, and Del smoked cigars. Shannon would have to roll the window down and stick his head out of the car to smoke, just so Max wouldn’t get sick and cough. They arrived in New York and stayed at the Forrest Hotel where Micahnik and Balk had them booked. On January 21st, 1961, they walked into Bell Sound recording studios with all of Max Crook’s crazy gadgets and equipment. Bell Sound was one the first professional 4-track recording studios in the world at the time, and Balk and Micahnik were willing to pay the top dollar to get a professional recording slicked. “All the big hits came out of Bell Sound at the time,” commented Harry Balk in a 1997 interview.

Shannon again was nervous in the recording studio, as he felt overshadowed by such talented musicians. “Del was surrounded by these great guys,” recalled Max Crook. “You have to understand, Del was this small town guy who was self-taught when it came to playing music. Here were all of these now famous session men like Al Caiola, Milt Hinton, and Bill Ramal who could read music charts and play licks like you wouldn’t believe. Bill Ramal was a master of arrangements, and here was Del, just a guy who wrote a hit song.”

Max Crook was a brilliant and genius fellow. He set up his musitron in the recording studio as the session men and engineers gawked. “What is he doing” they would ask. Harry Balk produced the session, running around the place with an iron fist. “Do this, do that. Plug that cord in. I don’t want to hear it, it’s not open for discussion. Get it done.” Balk was an ace at producing. He had a great ear for music and sound, and used threats and force as a means to accomplish what he needed done in a hurry! Balk was a good organizer, and he chose his session players carefully. He told Del that he would not be playing his guitar on the session, that vocals would all that he’d be doing. Shannon was upset about that, desperately wanting to play guitar on his own session, but Balk felt that because Del couldn’t read music charts, he’d have to allow Al Caiola to play in his place. Although Shannon was an accomplished guitarist, he was never given much opportunity to play it in his years with Bigtop.

The recording session lasted just three hours, and everyone seemed to know they had laid down a few good tracks. Runaway was played to distributors via a telephone hook-up in the control room, where distributors across the country could hear a rough mix and pre-order before it went to press.

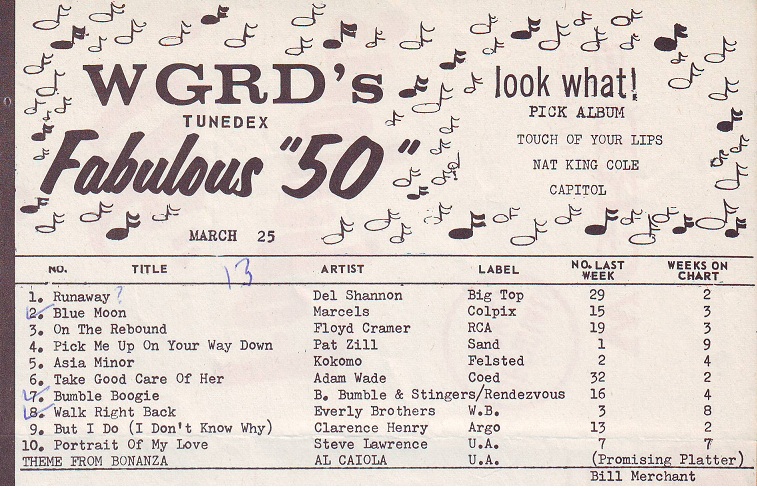

Runaway was released on Bigtop Records in February of 1961 and it began immediately to climb the charts. By March, Balk was on the phone calling Shannon at the club and telling him Runaway was indeed a runaway…selling 80,000 records a day. Shannon asked if that meant he could quit the club. Harry replied in the affirmative and told Shannon to get to New York as quickly as possible. A show had been scheduled at the Paramount Theatre in Brooklyn. In April, Shannon appeared on Dick Clark’s “American Bandstand,” helping to catapult Runaway to the #1 spot on the Billboard charts where it remained for four weeks. Runaway made Shannon an instant star. His bio was written by his manager Irving Micahnik, who changed the married 26 year old singer with two kids into a 21 year old milk drinking superstar, unmarried and available to all young women, with no attachments. When wife Shirley traveled with him on tour, she was billed as his sister. Shannon was not allowed to play guitar on stage. He was forced to wear iron-pressed suits and snap his fingers like Frank Sinatra. This was not an uncommon practice. Shannon sang his only hit Runaway four times a day at the Paramount.

Shannon was fortunate to get a brief break near the end of April ’61 to visit his hometown of Coopersville, where he was asked to speak to the high school teenagers about music, his success, and his stardom. Shannon was joined by his mother and father, and felt he had finally proven himself in the eyes of many in his hometown, including his high school principal, Russell Conran, who mentored Shannon and managed to keep him in school. Shannon had very high regard for this man and in later years always made a point of visiting him as if he were family. But the small town thinking still lurked in the background. Shannon was not allowed to sing Runaway to the high school student body. It was feared by the school faculty that if Shannon sang, the youngsters would get out of control. After his speech, Shannon was to receive the key to the city from the Coopersville mayor. The mayor never showed up. Rock and Roll was not yet accepted in this small town, much in the same respect as blacks or Hispanics. The idea of “keeping the town clean” and “free of sinful things” was a very common practice in those days. That night, Shannon played Runaway and a few other numbers on Main Street in downtown Coopersville on the back on a flatbed truck. Max Crook joined him. Police protection was necessary in case a riot or frenzy broke loose.

Del returned to New York in May with Max in tow to record his follow-up single, Hats Off To Larry, a song he’d written in the dressing room at the Paramount, with Bobby Vee and Dion present. Bobby and Dion took the farm boy out of Shannon and slicked him up with a new hairstyle and some Italian suits. Hats Off To Larry was Shannon’s only original tune recorded at this second session, his other songs having no commercial appeal in the eyes of Balk. Instead, Balk went to the Brill Building and picked up Arthur Altman and Wilbur Meshel’s Don’t Gild The Lily Lily, Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s I Wake Up Crying (which became a hit for Chuck Jackson), and Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman’s Wide Wide World. Shannon supplied only vocals, while session ace Al Caiola played guitar. Milt Hinton played bass, Joe Marshall was on drums, Max Crook on piano and musitron, and Bill Ramal on saxophone. The session was recorded at Bell Sound Studios with Harry Balk producing, Bill Ramal arranging, and Bill MacMeekin engineering.

Hats Off To Larry was released in the summer of 1961 and took the fifth spot on the charts as Runaway worked its way down. With a second hit on their hands, Balk brought Shannon back into the studios to cut a few more tracks to make an album. Shannon had some material worthy of recording, including Daydreams, The Prom, Lies, and He Doesn’t Care. Balk chose two Pomus/Shuman numbers for Shannon to record, Misery and His Latest Flame, the latter being later recorded by Elvis. Shannon’s previous recordings of The Search and I’ll Always Love You rounded out the album. In truth, the latter two probably should have never seen the light of day. Hats Off To Larry and Don’t Gild The Lily, Lily would have been a better choices, but it those days the record charts were still being driven by sales of singles, and Balk and Micahnik didn’t want an album to take away from the sales of the new single. ‘Runaway with Del Shannon’ was released in late summer, with 10,000 units being pressed (9,000 in mono and 1,000 in true stereo). The LP didn’t fare well on the album charts.

In August of ’61, Shannon recorded So Long Baby and The Answer To Everything, this time at New York’s Mira Sound. Shannon had been touring extensively and hadn’t had much time to write more songs. It was another split session, with Max Crook recording two instrumentals, the original Twistin’ Ghost, and a cleverly layered The Breeze and I & Theme from Peter Gunn (two standards put atop one another to give them a fresh sound). So Long Baby went to #28 on the American charts. In October, Shannon and Crook returned to the studio, recording another split session with Shannon’s Hey! Little Girl and I Don’t Care Anymore and Crook’s Greyhound and Autumn Mood. Hey! Little Girl also broke the American Top 40 at #38, giving Shannon a string of four hits in just his first year as a recording artist. Crook also faired well, having regional hits with both “Maximilian” singles in Canada.

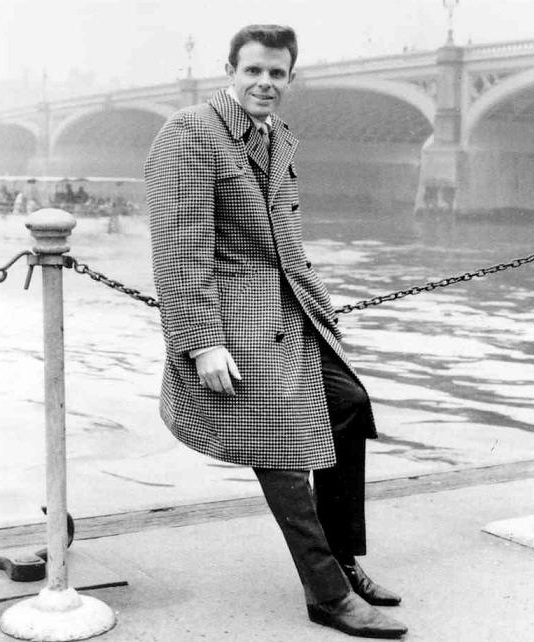

In February 1962, a deal was struck by Irving Micahnik for Shannon to appear in an upcoming British film, ‘It’s Trad Dad,’ with Craig Douglas and Helen Shapiro. For his next single, Shannon was talked into recording Pomus and Shuman’s Ginny In The Mirror and You Never Talked About Me, two songs intended specifically for the film. Shannon managed to work in an original, I Won’t Be There, which featured a roller coaster ride of soaring vocals. Bucky Pizzarelli replaced Al Caiola as session guitarist, and a session pianist replaced Max Crook. Ginny In the Mirror bombed miserably, and soured Harry Balk who was against the session to begin with. Balk advised Micahnik he was going to fly out Shannon to Nashville to search for new material and a new sound. In Nashville, they found what they were looking for: Roger Miller’s The Swiss Maid. Del recorded two originals, Cry Myself To Sleep and I’m Gonna Move On, during the first night at Columbia Studios on May 8, 1962. Harry Balk’s wife, Patti Jerome, cut two sides for her next Bigtop release. The next evening, Shannon recorded four more songs, The Swiss Maid, Cindy Walker’s Dream Baby, and a song that Dickey Lee had cowritten for George Jones, She Thinks I Still Care. Dion’s Runaround Sue rounded out the session. Boots Randolph and the Jordanaires were featured, among other Nashville regulars. Cry Myself To Sleep didn’t do much in the American market, but in England, it fared well, and inspired Elton John’s Crocodile Rock. The Swiss Maid soon followed, missing completely with the U.S. market, but breaking in at #2 in the U.K., and doing very well all across Europe. Another British tour was lined up, and Shannon toured heavily to promote his latest effort. Del continued to write songs with regularity. He walked into Belinda in London to lay down a few songs to acetate. Things She Said and I’m Losing You. Neither would see the light of day, but are available here for the very first time.

Balk noticed a writing freeze in Del, and decided to team him up with Bigtop writer, Maron McKenzie. Maron, who went by the nickname Robert, was a staff writer for Balk and Micahnik, whose work included tunes for some of their artists, including Bobbie Smith & the Dreamgirls, Mickey Denton, Spencer Sterling, the Volumes, Don and Juan, and the Young Sisters. McKenzie wrote Casanova Brown/My Guy for the Young Sisters about the same time that Shannon recorded The Swiss Maid. The Young Sisters took Casanova Brown to #93 on the charts September 29, 1962 for one week. They were a team of three Italian sisters from the east side of Detroit, and they had a great “locomotion-like” sound. McKenzie came to Shannon’s house in Southfield, Michigan with the idea for Little Town Flirt, a song he was penning for the Young Sisters’ follow-up. Shannon liked the idea and together he and Maron finished the song. Shannon had been influenced by the Nashville guitar playing, double-strumming, which later became known as the Mersey beat sound. Shannon had The Wamboo already in the bag, and it was a perfect B-side for Flirt. Balk set up another session for November and Shannon recorded Little Town Flirt and The Wamboo with the Young Sisters doing background vocals. At the same session, the Young Sisters recorded McKenzie’s Playgirl and Hello Baby, which Balk released on his own label, Twirl Records.

“I remember writing with Del,” explained Robert McKenzie over the phone recently. “We ate bologna sandwiches and wrote Little Town Flirt. ‘Here she comes, walkin’ down the street.’ No no! ‘Here she comes, that little town flirt.’ We worked it out. I had this idea, ‘the temptation of those ruby red lips.’ Del changed it. ‘the temptation of her tender red lips.’ It was wonderful working with Del. He had the idea of ‘paper heart’ and ‘tear it apart.’ It all worked out. We followed that up. I had the idea for Two Kind of Teardops and he had the idea of Kelly. We wrote them together. Two Silhouettes was his, My Wild One was mine. Co-writing with Del was a fun experience, one I’ll never forget.”

Little Town Flirt took a few weeks to break as Christmas singles were interfering with regular airplay. In late December, when Christmas had passed, Flirt shot like a bullet from #88 to #12 in just a couple of weeks. Shannon had another hit and a different sound. Del and Robert got back together to write Two Kinds of Teardrops, Kelly, Two Silhouettes, and My Wild One. Shannon called Harry. “Balk, I need another recording session set up! Let’s use the girls again for these songs.” On February 21, 1963, he recorded the four songs at Bell Sound, with the Young Sisters backing him up. Two Kinds of Teardrops was released to follow up Flirt and it was another silver record. Del Shannon was back on top, both in America and in Europe. Shannon flew to England where he toured heavily on the success of Little Town Flirt and to push Two Kinds of Teardrops. He also visited Sweden, where he was popular. Kelly, although a B-side, received airplay in Liverpool where it became a hit.

Shannon returned to Bell Sound in New York to fill out an album’s worth of songs. Recorded for the Little Town Flirt album were Bruce Channel’s Hey Baby, the Goffin/King composition Go Away Little Girl, and Happiness, a tune Shannon co-wrote in 1960 with a Battle Creek local named Jim Ellis.

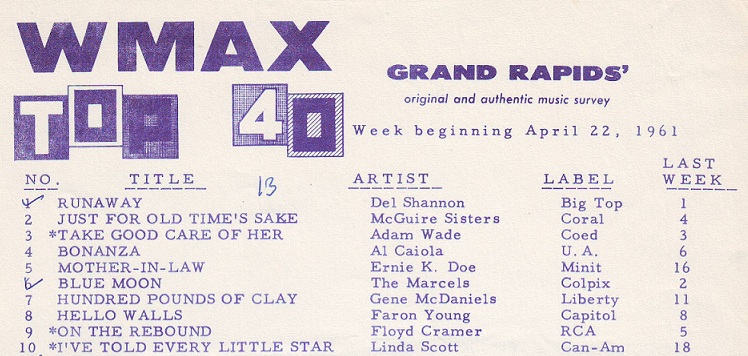

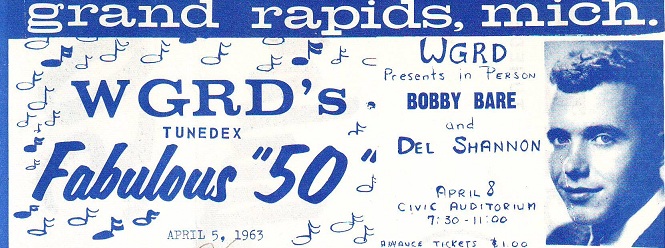

On April 8, 1968, Del Shannon performed at the Civic Auditorium in Grand Rapids with Bobby Bare:

Shannon shared the bill with the up and coming Beatles at the Royal Albert Hall on April 18, 1963, closing the show with Flirt and Teardrops. The Beatles took the stage just before him, playing From Me To You and Twist and Shout. Shannon was struck by From Me To You, and told John Lennon he was going to record it. Shannon loved the use of the A-minor chord in the middle of the bridge, and set up a recording session at West End Studios. On May 1, 1963, Shannon cut his own version of From Me To You, Linda Scott’s Town Crier, and two original compositions, Little Sandy and Walk Like An Angel. Ivor Raymonde was the arranger at the session. Shannon produced. Johnny Tillotson, who was touring with Shannon, attended the session, along with Irving Micahnik, who was also present. Two days after the recording session, Shannon played Town Crier over the air on BBC radio’s ‘Go Man Go’ show. This was the only time this recording was heard publicly. Micahnik took possession of the master tapes and they were later lost. Only From Me To You surfaced as the A-side of Shannon’s next and last Bigtop single.

Del, upset with late royalties and deals going sour, left Talent Artists, Inc. and Bigtop and searched for another label. Micahnik made sure that was not going to happen. He mailed letters and called all of the major record labels, threatening lawsuits if anyone signed Del Shannon. Irving had gone to law school and was very good at threatening legal action. Shannon was blackballed in the music business, and his only solution was to form his own record label, Ber-Lee Records, named after his parents. In August of 1963, Shannon booked 3 hours of time at Bell Sound to record four sides for Ber-Lee: Sue’s Gotta Be Mine, Now She’s Gone, That’s The Way Love Is, and Time of the Day. He hired Bill Ramal to arrange the session, and Del produced the set himself. Bucky Pizzarelli was brought in on guitar, Joe Benjamin on bass, Osie Johnson on drums, and an unidentified pianist. Shannon played rhythm guitar. The first Ber-Lee single was Sue’s Gotta Be Mine coupled with Now She’s Gone. Sue made it to #71 in the U.S. and #21 on the U.K. charts. Shannon later said that distribution of the single was to blame as it was hard to get records out to the distributors in a timely manner. He contracted with Diamond Records to help out with distribution. Apex Records released it in Canada, and London distributed it in England. Shannon released That’s The Way Love Is b/w Time of the Day in early 1964 before returning to Harry and Irving. By this time, they had terminated their deal with Bigtop Records. Rumor was that Micahnik owed money to both Bell and Mira Sound studios, and both studios were hounding Johnny Beinstock, president of Bigtop Records, for money. Beinstock paid the bill to deny Irving access to the master tapes, and severed all partnerships with Talent Artists, Inc. Thus most of Del Shannon’s master tapes were lost. Most masters were normally kept at the recording studio vaults so that they would be close at-hand if anything needed to be done with or to them.

About this same time, Shannon fooled around in United Sound studios to record a few numbers with Dick Bosie and the Teenbeats, who were also with BigTop at one point. Most of the session yielded surf-type music, jam sessions recorded by the bunch of which Shannon produced and paid for. Among the tracks wereNothin’, Pursuit, and Torture, an instrumental with overdubbed vocals by Del and the Teenbeats being “whipped” and begging for water. The final track at the session was a novelty tune by Del and his son Craig called Froggy. Froggy was a silly song and never intended for commercial release. It was Shannon’s first time bringing in one of his children to a recording session, and Craig was allowed to sing the frog’s voice (slowed down to give it depth) while Shannon sang the high female part (sped up to give it more female quality). This session is being released in it’s entirety here for the first time by Bear Family for reasons of historical completion . (We hope that Del would approve).

Balk and Micahnik sent Shannon into the studios with the Royaltones as his backing group. The new deal allowed for Shannon to play rhythm guitar at his own sessions. Dennis Coffey played lead guitar, Bill Knight played second guitar, Bob Kreiner played bass, Marcus Terry played drums, and George Katsakis played piano and organ. The Popoff brothers, Greg and Mike, played alto and tenor saxophone. Bill Ramal was now out of the picture. The Royaltones also substituted as Shannon’s vocal chorus. Mary Jane, Stains On My Letter, I’ll Be Lonely Tomorrow, and I Can’t Fool Around Anymore were cut at the February ’64 session. McKenzie was brought in again as co-writer for Mary Jane and I’ll Be Lonely Tomorrow. Shannon co-wrote I Can’t Fool Around Anymore with guitarist Dennis Coffey and Katsakis, the organ player.

Unfortunately, Shannon had two singles released the very same day: That’s The Way Love Is (Ber-Lee) and Mary Jane on Amy Records (a subsidiary of Bell). In Britain, That’s The Way Love Is was ignored, but Mary Jane, issued on Stateside Records, did well, breaking in at #35. Split airplay caused the two singles to compete against one another, and both failed in virtually every country.

Harry Balk felt Shannon’s songwriting had gone into a temporary slump. Shannon was still upset over legal battles, but eventually signed over his Ber-Lee sides to Micahnik. Balk had a thought. “Del, do you know the song ‘Handy Man’?” Shannon said that he did. “Well I don’t want you to play it the way Jimmy Jones recorded it,” Harry said, “I want you and the Royaltones to come up with a new arrangement, and then we will cut it.” Shannon agreed, and met up with the Royaltones who were touring in Pennsylvania. In April 1964 Del and the Royaltones came in to record Handy Man, the Impalas’ Sorry (I Ran All the Way Home), and Shannon’s original Give Her Lots of Lovin’. Handy Man took the majority of the session to record. Shannon and Balk feuded over the arrangement, and Balk eventually got his way. Balk ran the studio with an iron fist. “This is how I want it, da dee da da, ba boom ba ba!” Harry explained in a 1997 interview. “I didn’t want the record to be a copy-cat of the Jimmy Jones hit. We needed a whiter arrangement. Del had pissed me off because he didn’t do what I asked him, and that was to find a new arrangement for the song.” Despite the feud, good things came out of the argument and Handy Man came out really tough and tight. Only one hour was left to record both “Give Her Lots of Lovin’” and “Sorry (I Ran All the Way Home). Del worked on Give Her Lots of Lovin’ as Harry sucked his thumb. “This song sucks Del. Wrap it up and let’s move to the next one.” Sorry (I Ran All the Way Home) was cut in just three hasty takes, clocking in at 1 minute 47 seconds. The session was over. “Handy Man’s your single Del!” Balk exclaimed.

Handy Man made #22 in the U.S., beating the U.K. #36 spot. Shannon was a major hit maker stateside again, and everyone felt an album was due. In late June, Shannon quick covered five songs: Memphis, Ruby Baby, Crying, World Without Love, and Twist and Shout. “He loved Roy Orbison’s ‘Crying’,” Shirley Westover commented one night in August 1999. “He actually cried when he heard that song. He so wished that he was the one that wrote that song. He loved Roy’s music so much, he would always cry.” An album titled ‘Handy Man’ was released on Amy Records in mono form. It is believed that the album was released in stereo also, but no known copy has been reported to exist. The album cover does have “stereo” lettering on all mono sleeves, if the label is peeled back from the creased border. If a stereo copy is ever found, it would become the only known copy of these tracks in true stereo, as the master tapes are lost.

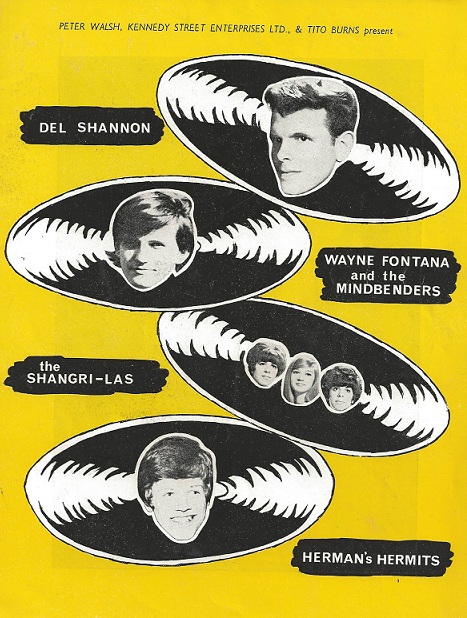

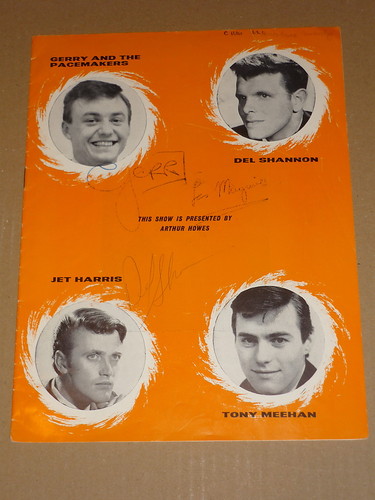

Various undated Del Shannon concert brochures:

In August of 1964, Shannon tried to repeat the success of Handy Man with another revival, Bobby Freeman’s Do You Wanna Dance. George Katsakis played a clavioline, a synthesizer much the same as Max Crook’s musitron. Recorded at Mira Sound, the track sound seemed distorted. “This was not intentional, I assure you,” explained Harry Balk in 1997. “Mira was inferior to Bell Sound, but Bell was booked solid, so we had to go with Mira. We decided to cover ‘Handy Man,’ and when we had success with that, we copy-catted ourselves and cut another cover. Damn! Looking back, I don’t think we should have cut ‘Do You Wanna Dance’.” Nevertheless, Do You Wanna Dance nearly cracked the Top 40 in the U.S. and became a staple in Del Shannon’s live sets, normally his closing/encore number behind Runaway. Del certainly had mastered this song live, and he got the audiences up off their seats. This same session yielded the B-side This Is All I Have To Give, a number that Shannon wrote prior to Runaway and originally dubbed Everything I Have Is Yours. This session also included Shannon’s first attempt at recording I Go To Pieces. According to Harry Balk, Shannon had been drinking and wasn’t able to hit the right notes. Harry said he couldn’t believe a guy could write such a great song but then not be able to sing and play it. The three hour session was over, and Pieces wasn’t completed. The song was scrapped and the single was all that was utilized from this session. Shannon originally wrote I Go To Pieces for a black singer named Lloyd Brown, whom Shannon had discovered one night at a Battle Creek club called the Black and Tan. Shannon wrote Pieces in an R & B style, and so he never thought of recording the song for himself. Produced and arranged by Del, the acetate of I Go To Pieces by Lloyd Brown included the flipside The Zombie, a dance stomper much in the vein of The Wamboo. A cheesy B-side, this freaky bottom coupler was also penned by Shannon, but never released. I Go To Pieces was shopped to Mercury Records and Chess Records. Both turned it down.

Lloyd Brown on the drums at the Mousetrap in Grand Rapids:

Soon after, Shannon toured Australia, and on the tour were the British duo Peter & Gordon. He played the record for them, and they agreed it was a great tune. They asked to record it and Shannon obliged. A few months later, Peter & Gordon took it to the bank: Top 10 on the charts and a big smash internationally. With an arrangement change, the song had more feel, and Shannon was both excited and devastated, for his song was a hit, but he wasn’t the one who recorded it. Shannon always said in interviews years later that I Go To Pieces was his favorite song among all the songs in his repertoire. Gordon Waller admitted at the 1999 Beatlefest convention where he played Pieces live, that it was still his favorite Peter & Gordon song. “It has lasting power,” he commented.

Del continued to write successfully when, inspired by his friends Stephen Monahan and Dan Bourgoise one night in his home basement, he was encouraged to write another song in A-minor. Shannon took the advice of Bourgoise and started strumming his guitar one night, singing “…if we gotta keep on the run, we’ll follow the sun” as Monahan sang “wee-ooo” in falsetto as a gag. Shannon passed out from drinking that night, but the next morning, he woke up with “We gotta keep searchin’ searchin’” in his head. He pressed ‘Record’ on his reel-to-reel and laid down a decent demo. Stranger In Town popped out of his head a day later, along with Over You, both featuring the influence of Roy Orbison. Broken Promises soon followed and Shannon had another recording session to set up. Four self-penned items. Shannon was on a hot writing streak. The Royaltones were called up and everyone rallied at Bell Sound in October of 1964 and recorded the four songs. The production on this session was very intense and tight. Balk got out on the studio floor himself with a big fat cigar dangling from his mouth and clapped two wooden ‘two-by-fours’ blocks together for added effect. “We echoed the f–k out of it” Shannon would later tell Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne in the studios while recording his last album, ‘Rock On!’ Shannon had his next two singles in the bag, and they were hot! Keep Searchin’ went Top 10 in the U.S. and #4 in England. Stranger In Town followed on its heels, #30 in America and #40 in the U.K. Shannon enjoyed a third string of hits, and toured Great Britain again, this time with Roy Orbison. He was presented with a new cherry red Gibson guitar from Merle Lemmon, a friend of his who worked for Gibson. Merle had ‘Del Shannon’ embossed into the neck and pick guard of the ES 335 model guitar. The guitar featured a mink strap and a double pick guard, something very uncommonly seen. It had a very presentable look to it. Shannon looked his career best in the 1964-1965 era, with this guitar, his perfectly combed hair, and his shiny suits. His voice never sounded better.

Shannon had time around the holidays, and wanted to record a country album. Though Micahnik and Balk both believed this was a bad idea, they pacified Del by allowing him to record a Hank Williams tribute album. “We cut it at United Sound in Detroit,” recalled Harry. “I wasn’t about to spend a lot of money to fly everyone to New York to record a C&W thing. I mean, I didn’t believe in the album, and I didn’t like the idea of doing it. But Del persisted and persisted, and so I finally caved in. ‘Yeah, let him do it’ I said.” Shannon had a ball. He brought in the Royaltones and his friend Buddy Gibson, who played steel guitar. Gibson was a friend who had played with Shannon at a dive club called Daisy Mae’s Tavern in the old days near Gun Lake in Wayland, Michigan. Shannon arranged the album tracks himself. Dan Bourgoise, Stephen Monahan, and Doug Brown (later of Bob Seger fame) popped into the studio to watch. Shannon loved country music and this is what he really wanted to do. Balk and Micahnik did their best to keep him in the rock vein. Shannon recorded a few more tracks in similar style, including Wrong Day, Wrong Way, Table Reserved for the Blues, Pardon Me (I Guess I’m In the Way), and Queen of the Honky Tonks. None included here have previously been released until now on this set, directly transferred from the two-track session stereo master tapes.

When Shannon came off tour in March of 1965, a two day recording session was set for him at Bell Sound to cut his next single Break Up b/w Why Don’t You Tell Him and an album’s worth of tracks. He chose some current material including Jay and the Americans’ She Cried, the Searchers’ Needles and Pins, Gene Pitney’s I’m Gonna Be Strong, the Four Season’s Rag Doll, and Roy Orbison’s Running Scared. Shannon also took another stab at I Go To Pieces with the Peter & Gordon arrangement. He nailed it down and that rounded out his album which was titled ‘One Thousand Six Hundred Sixty One Seconds with Del Shannon.’ The album, released in the states on Amy Records, sold well, showcasing some of Del’s finest work. The album was also released in a very collectible true stereo version.

Shannon’s album was advertised and released about the same time as his next single, Move It On Over, a rocking song co-written with Dennis Coffey, which had a hard driving edge to it that was very early punk. He kicked off the summer with this rocker but it didn’t prevail. It failed with AM radio and Shannon was furious. “I want out of this business,” he yelled out on Gun Lake, a town between Battle Creek and Grand Rapids, Michigan. Friend Dan Bourgoise remembered that time. “Del was upset that both ‘Break Up’ and ‘Move It On Over’ bombed. He thought he was staying on the cutting edge with a new sound, but neither songs were accepted by the public. He sailed copies of the 45’s into the lake. Not one or two, but a whole box of 45’s! One at a time. ‘Forget this, I want out!’ he said. I tried to calm him down and yelled, ‘The record’s great! You’re crazy Del!’” It was at this time Shannon started considering either moving to California, moving to Nashville, or giving up all together.

Shannon was now at a fork in the road as the peak of his fame began to move in the downward direction. He recorded some jazz tunes at Spectra Sound, This Feeling Called Love and It’s Funny, both very Frank Sinatra-like. He was writing jazz tunes, country songs, rock numbers, and struggled with what vein of music he should stay with or move into.

Although Move It On Over bombed, and the flipside, She Still Remembers Tony, was one of the worst B-sides Shannon had ever recorded, the Pepsi-Cola jingles that were recorded at the session were heavily airplayed, and that kept Shannon in the limelight. Near the end of the summer of ’65, Balk called Shannon back to the studios to cut another session, with the intention of releasing a fourth album on Amy Records. Game of Love, No One Knows, Tired of Waiting for You, My Love Has Gone, and Tell Her No were recorded. Unfortunately, very soon after, Shannon had a falling out again with Micahnik and Balk, this time parting company for good. Irving Micahnik and been allegedly withholding back a lot of royalties due Shannon and other artists from their stable, along with monies due Harry Balk. Balk too separated ties with Micahnik. “I couldn’t deal with him any longer,” Harry explained. “I liked the guy, but he had a gambling problem and played the ponies. When he couldn’t cover his bets, he took royalty monies owed to artists and paid off his bookies. I sold out my interest of the music in Twirl Records and Vicki Music to Irving and formed Impact Records and Gomba Music. This was around 1966.” Shannon’s forthcoming album was never released. Irving threatened legal action against Del, as he was under contract for one more single. Shannon, unable to be released from his contract and move on with his career until he complied, agreed to record one more single. “I told Irving I’d sing whatever the hell he wanted me to sing,” Shannon admitted in a 1981 interview, “but I would be damned if I would give up publishing of two more songs to him. So I cut ‘I Can’t Believe My Ears’ and ‘I Wish I Wasn’t Me Tonight.’ They reminded me of ‘Don’t Gild the Lily, Lily’ and ‘Ginny In the Mirror.’ I hated those songs!”

In 1966, Shannon was free from his contract to Talent Artists, Inc. He spent some time in California with Tommy Boyce, who had sold Del on the idea of eternal sunshine and west coast happiness. Tommy wanted Del to sign with Colgems, a small label with silver screen ties. Shannon declined. “I wanted to get signed to a big label. Capitol, RCA, you know, someone big!” Shannon explained in a 1982 interview in New York City. “The last thing on earth that I wanted was to be signed to an indie (label) again with another Irving Micahnik.” Eventually, Shannon found what he thought he was looking for. Liberty Records offered Shannon a great contract and a large advance. A large label meant money to back him, heavy promotion, and a large distribution base to get the records out. Shannon called his wife Shirley on the telephone. “I’m here with Tommy Boyce,” she recalls him saying, “California is great!” Shannon called his friend Dan Bourgoise, who was still living in Michigan. “Danny,” Shannon said, “Can you help Shirley winterize the house and help move her and the kids out here? California is where it’s all happen’ man!” So Dan and Shirley packed up and drove out to California by car caravan style in Shannon’s Chevy Corvair and Cadillac.

Liberty Records was anxious to get a record out, and put Shannon with Tommy “Snuff” Garrett and Leon Russell to produce his first session for them. In February 1966, Shannon recorded his first Liberty single, The Big Hurt, a cover of the 1959 Toni Fisher hit written by Wayne Shanklin. Dan Bourgoise remembers the session. “Del was really excited. He was in sunny California, with a new label, with new people, and had really high hopes and expectations for first single with Liberty. His last three singles had bombed, and Del was very eager to get another hit on the charts.” According to Bourgoise, the “phasing” effect on The Big Hurt was created by the engineer, Henry Lewy, who put his hand on the reel to slow the master tape down, and then let it catch up to itself again when they were dubbing the single master down to mono. This is why the phasing effect is only available on the mono take. With the EMI ‘Liberty Years’ release in 1991, a modern technique was used to try and re-create the phasing effect in true stereo, but it didn’t quite capture the magic that was produced on the mono single. Shannon cut two more sides at the session, I’ve Got It Bad, the B-side, and Show Me, which was another strong track and intended for a forthcoming single. Show Me actually became the third single for Shannon on Liberty, and without a B-side in the can, they retitled I Got It Bad as Never Thought I Could and released it again.

In 1966, Liberty Records was an album-driven label. Bobby Vee, who was also signed to Liberty, was selling many albums for the company, and it was felt that Shannon too could sell a vast quantity of albums. After all, Shannon’s ‘Little Town Flirt’ album was a huge success, peaking at #12 on the LP charts. Within two months of recording The Big Hurt, Shannon was back in the studios cutting ten more sides to round out an album. Included in the bunch was the follow-up single, For A Little While/Hey, Little Star, both penned by Shannon himself. In the mix were seven covers that Liberty executives wanted Shannon to record. “Ok Del, let’s look at what’s climbing the charts. Do ‘When You Walk In The Room,’ ‘It’s Too Late,’ ‘The Cheater,’ and ‘Kicks.’ You sound like Lou Christie so why don’t you go ahead and cut ‘Lightnin’ Strikes’ too.” It was this kind of mentality, and Shannon wasn’t really pushed to write his own songs. He was encouraged to kick back, take it easy, and let Liberty take care of it. Tommy Boyce approached Del with Action. He declined. Dick Clark called Shannon and asked him to record it for his new show ‘Where The Action Is,’ in which the song would be used for the show’s theme, thus virtually guaranteeing Shannon both a hit single and heavy airplay. Shannon declined a second time. He loved Tommy Boyce but he thought the lyrics were rather silly. Boyce eventually talked him into doing the song, but it was Freddy Cannon who took it to the bank. Shannon selected Roy Orbison’s Oh, Pretty Woman, and Leon Russell pushed Everybody Loves A Clown on him. The session was a hurried one, and the mix on the album was not the best it could have been. The LP titled ‘This Is My Bag’ hit stores and sold moderately well, despite The Big Hurt reaching only #94 on the charts that spring. For A Little While and Show Me were issued behind The Big Hurt, but neither managed to grab any attention, despite both being very decent sides.

Liberty pressed on, teaming Shannon with in-house producer Dallas Smith in July. On the 19th, Shannon and Smith co-produced Under My Thumb, a Mick Jagger and Keith Richard composition. The production was very tight and tough. Shannon’s singing was better than ever, injecting feel into the song as if it were his own. In a way it was. It was Shannon’s idea, he was recording it his way, and everything was coming together magically in the studio. The B-side, She Was Mine, was a strong entry from Shannon and Roy Nievelt.

Seven days after recording Under My Thumb, Shannon hit the studios again to slick six more sides. Four cover tunes, Red Rubber Ball, Pied Piper, Sunny, and Time Won’t Let Me, were recorded along with two Shannon originals What Makes You Run and I Can’t Be True. Shannon was hoping for another single in the batch. Two days later, he returned to cut Summer In The City, Where Were You When I Needed You, and The Joker Went Wild. This rounded out enough tracks for a second album, ‘Total Commitment.’ Although better than ‘This Is My Bag,’ the album again had an assembly line mentality. “Get an album together and then get out there and push it!” Under My Thumb failed to chart on Billboard and Cashbox, but broke into the Top 10 in Oklahoma City and Washington D.C. Had ample airplay occurred on a national scale, Shannon would have enjoyed another big hit. The song was strong enough, but it just didn’t happen.

Depressed by a tough first year at Liberty, Shannon turned to friends Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, who were having great success in writing and producing the Monkees. “Hell Del, we’d love to record you!” commented Boyce, and he and Hart worked out a contract between Colgems, Liberty, and their publishing arms to make it happen. On the day of the deal, November 2, 1966, Shannon walked in to Hollywood Sound Recorders with Boyce, Hart, and his friend Max Crook to record She, a pounding puncher penned by Boyce and Hart, and two other Shannon originals, Stand Up and The House Where Nobody Lives. Crook had brought his musitron, and the Runaway magic returned. She had great potential. Stand Up and The House Where Nobody Lives featured Shannon’s trademark, and was saved for an intended follow-up to She.

Del Shannon heavily promoted She both in the U.S. and in the U.K. It began receiving airplay when the Monkees released their own version on their sophomore album, instantly killing off Shannon’s version. By that time, the Monkees were becoming too hot. Shannon toured the U.K. in January and February 1967 where, at the BBC studios, he bumped into Andrew Loog Oldham, producer of the Rolling Stones. Oldham said how much he had loved Shannon’s version of the Stones’ Under My Thumb, and wanted to record him. Shannon called Liberty Records and was told, “Yes, whatever the expense. Go cut with Andrew!”

Shannon was excited at the prospect of recording his dream album. Andrew Oldham was at the pinnacle of the business in Britain, and this was Shannon’s big chance. Unprepared to record an album, Shannon brought He Cheated to the table, and Shannon with Dan Bourgoise sat down and hashed out Silently one night in a hotel room. Oldham was bent on re-recording Runaway despite Shannon thinking it wasn’t a great idea. Oldham talked him into it, and Runaway ‘67 was born, complete with a full blown orchestra that included John Paul Jones, Nicky Hopkins, Jimmy Page, and many other British session stalwarts. Mick Jagger and the Small Faces stopped in at Olympic Studios in London to see the sessions evolve. Oldham had a tight family of artists, and had Immediate artists Billy Nicholls, Andrew Rose, David Skinner, and Jeremy Paul Solomons contribute songs for the album. Nicholls submitted Cut and Come Again, Led Along, and Friendly With You. He was a young songwriter somewhat like a British version of a Brian Hyland. Rose and Skinner, who recorded as Twice As Much, were like Peter and Gordon, and they contributed It’s My Feeling, Easy To Say, and the ever-powerful Life Is But Nothing. Jeremy Paul Solomons donated Mind Over Matter, and Shannon brought in My Love Has Gone, a song he truly enjoyed by a writer named Ross Watson. P.P. Arnold and Madelaine Bell made up Shannon’s vocal chorus, and Arthur Greenslade arranged the session. The sessions were a painstakingly crammed four-day run, from February 23rd through 26th, 1967.

Led Along became the first single released from the bunch, but failed to chart in America. Mind Over Matter became the U.K. single with Led Along as its B-side. Still, the single failed to make any noise. Runaway ‘67 was released in August, getting some great exposure, but not re-kindling the magic of the original. Runaway ‘67 made #112 on the U.S. charts. Incredibly, it made the Top 20 in Australia! With the failure of the singles, the album was scrapped by Liberty before it was even pressed. Oldham had the L.P. ready to go, titling it ‘Home and Away.’ It was shelved…for 10 years. It was released as a compilation with three other tracks in the late 1970s as ‘And The Music Plays On.’

In light of what was happening in popular culture, Shannon was encouraged and pushed into doing a psychedelic album. He was encouraged to write the songs this time, and ‘The Further Adventures of Charles Westover’ began taking shape. Shannon took a risk and allowed junior producers Dugg Brown (formerly known as Doug Brown of Bob Seger affiliation) and Dan Bourgoise to produce the album. ‘The Further Adventures’ began with a session in September 1967 that yielded Thinkin’ It Over, a song that had been written on a piano at Shannon’s house by Del and Dugg Brown. A cover of the Box Tops’ The Letter was also recorded to 4-track for release as a single in the Philippines. Shannon was so hot in the Philippines, that many of his covers were Top 10 hits. Among the bunch were Sunny, Lightnin’ Strikes, The Joker Went Wild, and several others that dented the Top 20. Shannon made a quick tour to Manila, bringing along his wife for companionship. He admitted he didn’t know the words by heart to many of the songs he had covered for Liberty, so Shirley Westover stood in the orchestra pit at the front of the stage and held cardboard signs with the words to Sunny and others, so that Shannon could play his string of hits.

November 13, 1967 brought four additional tracks needed for ‘The Further Adventures of Charles Westover.’ River Cool, Colour Flashing Hair, Conquer, and New Orleans (Mardi Gras) included Dr. John on keyboards and Bob Evans (later of “Smith” fame) on drums. Don Peake arranged, and Shannon poured everything into this session. Bourgoise remembers, “We found this great tape loop at Liberty, called ‘Mardi Gras,’ and we used it on the tail of Del’s ‘New Orleans’ track. Del whispered and chanted throughout the song. Ahhh, it was great! Dugg Brown contributed the song to the session. He produced a band called Southwind on Blue Thumb. Jim Pulte wrote the song. Their version is pretty good too!”

December 5, 1967 Shannon returned to Liberty Studio to finish off 7 more tracks necessary for completing the ‘Charles Westover’ album. Be My Friend was written and contributed by Dugg Brown. Silver Birch and Magical Musical Box were recorded as well, a co-share on the writing credits by Del with Jonathan M. Perkins of Britain (They also penned River Cool together). Shannon brought I Think I Love You and Gemini to the table, and Shannon and Brian Hyland co-wrote Been So Long. One great writing effort was the brief collaboration Shannon had with ex-Eddie Cochran girlfriend Sharon Sheeley. Together they cranked out Runnin’ On Back, a bitchin’ tune that reflected awesome anger and reminded some of Move It On Over. Both the song and production work were hot on this one!

Thinkin’ It Over/Runnin’ On Back and Gemini/Magical Musical Box were the only two singles from the album. Neither charted, but both became instant cult favorites. There was an oddness to Magical Musical Box: lots of harpsichord and paranoia. Thinkin’ It Over included a picture sleeve, the only Shannon 45rpm to have one in the United States. ‘Further Adventures’ was Shannon’s first album to be pressed with the majority of LP’s slicked in stereo. Only Disc Jockey copies were pressed in mono.

Del Shannon made one more attempt at Liberty to record a successful record. On July 15, 1968, he recorded his final session for Liberty with himself and Dan Bourgoise at the helm. They recorded Dee Clark’s Raindrops, Somethin’ To Write Home About (never released), and two co-compositions with Brian Hyland: You Don’t Love Me and Leavin’ You Behind. Raindrops coupled with You Don’t Love Me became Shannon’s tenth and final single for Liberty Records, but it too failed, and Shannon thought seriously about exploring other avenues in the music business. He began feeling “washed up.”

Shannon discovered country artist Johnny Carver one night at the Palomino Club in Los Angeles. He brought him to Liberty Records and had Carver signed to their Imperial subsidiary. He then brought the young Johnny Carver into the recording studios and donated two self-penned titles, Think About Her All the Time and One Way Or the Other. Both were arranged and produced solely by Shannon. Carver later went on to have a national hit with Tie A Yellow Ribbon.

Shannon took another stab at country amongst the middle of all of this. He got together with Jimmy Morris and together they recorded I’m Going Through It Too, a re-write of Shannon’s Table Reserved For The Blues, and Pardon Me.

Brian Hyland was just getting out of his rut with Dot Records when Shannon brought Hyland over to his house in California to stay for a few months. A few months turned into two years, and Hyland became the younger brother Shannon never had. Shannon negotiated a deal with the Trousdale Music publishing firm, and thus began the co-writing partnership of Shannon/Hyland. Shannon helped out his friend from Ann Arbor, Michigan, deejay Ollie McLaughlin, with a Shannon/Hyland composition How Can I Tell, which was given to Barbara Lewis to record. Go Go Girl was another tune written by the duo for Beth Moore, and I’ve Got Eyes For You was given to Waylon Jennings. Del and Brian soon put the emphasis on rebuilding Hyland’s career. Shannon became Brian Hyland’s unofficial manager and mentor, taking the junior and developing songwriter under his wing to produce his self-titled album, ‘Brian Hyland,’ for Uni Records. The album included two hits: the Curtis Mayfield cover Gypsy Woman shot to #3 and was a big smash nationwide, followed up by the Jackie Wilson cover Lonely Teardrops, which made the Top 40. The album included Shannon on background vocals and guitar, and Max Crook on the keyboards, including the Hammond B-3 and Moog.

Around this same time, Shannon also discovered the group Smith at the Rag Doll Club in L.A. He ditched their drummer and brought in Bob Evans as a replacement. He worked with the band for six months to shape their sound and arrangements. Shannon then approached Dunhill Records to get a recording contract for Smith. Dunhill also wanted Shannon on the label, and he agreed.

On April 16, 1969, Shannon recorded his first session with Dunhill producers Steve Barri and Joel Sill at Western Studios in Hollywood. Recorded were Comin’ Back To Me and Never Be the Same. Barri and Sill took production credit for Baby It’s You, though it was the Shannon arrangement of the same song that took Smith to #3 in the U.S. Shannon now had two Top 10 artists! On May 6th, he entered American Studios in Studio City, California with Smith to record his own Sweet Mary Lou and four songs by Smith: I Just Wanna Make Love To You, Tell Him No (the Rod Argent hit Tell Her No), The Last Time, and something called The Dam Song. Two days later, Shannon returned to Western Recorders to cut Colorado Rain and I’ve Got Eyes For You with Max Crook on organ.

Comin’ Back To Me/Sweet Mary Lou was released in June of 1969, bubbling under the hot 100 at #127 on the charts. Shannon attempted a second single with Dunhill, and in November of the same year, recorded and released Sister Isabelle/Colorado Rain. The single failed to move, and Shannon decided to carry on with production work for Brian Hyland.

In October of 1970, Shannon attempted one last session with Dunhill, but all the tracks have remained in the can to this day. Good Love, Sun Don’t Shine, Anita (I’m Walking On Fire), She Woke Me Up, and the great Tim Hardin number Reason To Believe were recorded at the Sound Factory in Hollywood on Selma. It’s vital to say that Max Crook played at this session. Shannon eventually cut loose from ABC-Dunhill and he began working with the Robb brothers at Cherokee Studios in Chatsworth, California. The Robbs were also signed to Dunhill at the time, and they collaborated on tracks for most of the early 1970s. Shannon hooked up with Dick Clark and joined the bandwagon of his contemporaries on nostalgia and oldies shows, and cut his infamous ‘Live In England’ album in December 1972.

In 1973, Shannon briefly hooked up with Electric Light Orchestra’s Jeff Lynne, and signed with Island Records for a couple of singles. In 1978, Tom Petty made the effort to search out Shannon and tempt him out of obscurity. Their collaboration resulted in a critically acclaimed album titled ‘Drop Down and Get Me,’ which included the Top 30 hit Sea of Love. In 1984 Shannon signed to Warner Brothers and headed to Nashville to become a country artist. Two singles were released, both scraping the country charts, but no album followed. Del and his wife of 30 years, Shirley Westover, divorced suddenly, having grown apart.

Del remarried to Bonnie LeAnne Tyson in 1986, and together they toured Japan in 1987, England in 1988, and Australia in early 1989. They formed CLAW Music and Shannon was again working with Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne in ’88 and ’89 for a creative effort to be titled ‘Rock On!’ when he unexpectedly committed suicide. His talents ended on the sad day of February 8, 1990. He was slated to replace Roy Orbison in the Traveling Wilburys all-star rock quintet, and Walk Away became his final single that he promoted on tour while still alive.

Del Shannon was honored with two Memorial Markers in Michigan, one in 1990 at the site where he wrote Runaway in Battle Creek, the other in his childhood home town of Coopersville in 1996. In March 1999 Shannon was inducted to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.</font>

Author, Brian Young, ©Copyright 2004